Capacity Building

Organizations of color leverage the power of collaboration

The childhood memories of Providence-raised James Monteiro are inundated with Black-led organizations and leaders who looked like him. He grew up on Howell Street. From his backyard, James watched construction crews build the East Side/Mt. Hope YMCA. His street was just outside the Lippitt Hill neighborhood of predominantly Black homes and businesses that were destroyed in the 1960s via eminent domain.

The late Billy Taylor nurtured James and his friends’ passions by holding talent shows so they could flaunt their Michael Jackson “Beat It” moves and convincing the city to shut down a street so they could race the wooden go-karts they built. Later in his life, James saw Barry O’Connor Jr. running enrollment services at the Community College of Rhode Island. That was his “aha moment” to pursue his calling.

There was also the Opportunities Industrialization Center of Rhode Island (OIC) that the late Michael Van Leesten created and led, as well as the Urban League of Rhode Island and the John Hope Settlement House, among others, that were thriving then.

“Those organizations that everybody went to were Black led,” said Monteiro, now 53 years old, “and now, I don’t know what happened. If you look at the major organizations that serve our people now, for the most part, we don’t lead them anymore.”

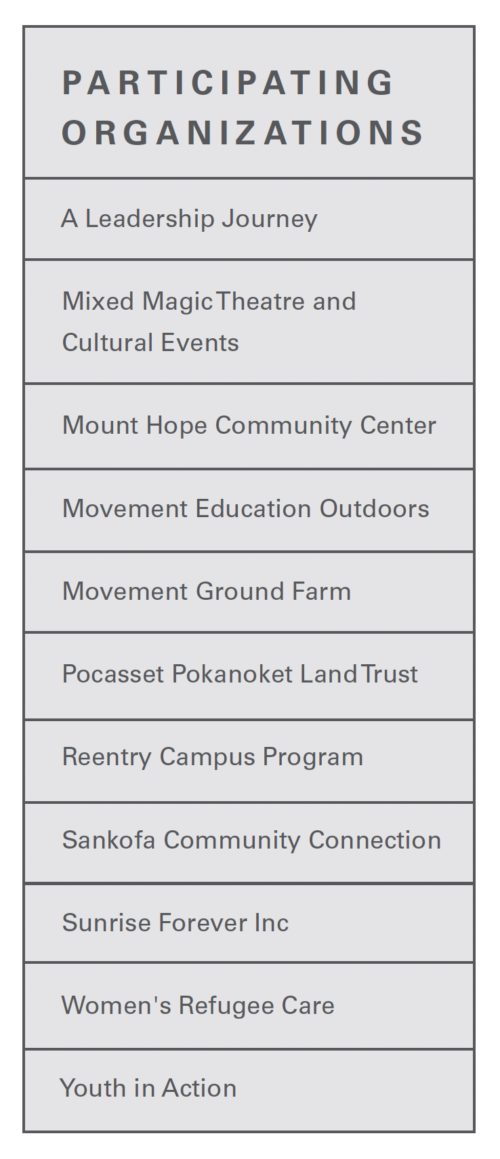

Launched in October 2021, the Rhode Island Foundation’s capacity building for nonprofits of color program is helping 11 organizations led by Black, Hispanic or Latino, Indigenous, Asian, and multiracial people (also referred to as BIPOC) to strengthen and extend their reach. The three-year program is part of the Foundation’s $8.5 million investment—above and beyond the existing annual funding—to address racial equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Thirty organizations applied for the first cohort, and the selected represent a diverse group of organizations in different stages of their development. They include a Providence community center, a youth-centered travel program, women’s refugee care organization, and an Indigenous land trust.

The Reentry Campus Program (RCP), which James Monteiro is the founder and director of, was also chosen. The Providence-based nonprofit’s mission is to improve access to and completion of post-secondary education for individuals who are transitioning from the incarceration system back into their communities. In addition to creating degree pathway plans for this population, the RCP also has a mentorship program and provides critical wrap-around services, continuous support, and resources specific to their individual needs.

“I love having the support of big foundations outside of Rhode Island, but it’s entirely another thing to be supported at home,” James shared. “That means the world, especially for people of color who are working in these spaces.”

He continued, “So when you are talking about building capacity, especially for minority-led organizations, I think you have to have the support of places such as the Rhode Island Foundation.”

This program and the Foundation’s Equity Leadership Initiative (ELI)—which cultivates, mentors, and seeks access for BIPOC individuals from across sectors to build a pipeline of leaders of color in positions of influence in Rhode Island—are part of the solution to close the many equity gaps plaguing our Ocean State. In both programs, the meetings are monthly, and the training and topics are shaped by the needs of the organizations who collaborate and give continuous feedback to program leaders.

In year one, a strategic communications planner gave a course to all the organizations and then met with each individually for an audit, with recommendations for improvement, of their current communication operations. They also had experts come in to improve fundraising efforts and strategies as well as data management and how to use data in storytelling. A retreat was also held for the organizations’ leaders to learn more about restorative/self-care practices.

Nearly all the leaders interviewed said the program gave them a rare opportunity to learn about each other’s organizations and how they could better support and collaborate with one another.

A cohort like this, organizations of color, has never been formed by the Foundation, so it in itself, was inspiring,” said Joann “Jo” Ayuso, founder and executive director of Movement Education Outdoors (MEO).

Movement Education Outdoors, also one of the 11 chosen, started in 2018 to work with youth and community organizations from Providence, Woonsocket, Central Falls, and Pawtucket to offer transformative outdoor experiences year-round—with the premise that all youths should have equitable chances to be in and enjoy outdoor activities. The activities include hiking, kayaking, snowshoeing, cross-country skiing, water and air quality testing, and mindfulness and movement practices.

The 11 to 13-year-old youths are also stewards of an urban garden (formerly Sidewalk Ends Farm) in the West End neighborhood of Providence. The gardeners practice organic and no-till farming as well as learn food justice education, Black and Indigenous mutual aid, and community building from guest educators and mentors of color.

Last summer, MEO youths also learned from another cohort organization, Mixed Magic Theatre (led by founders Bernadet and Ricardo Pitts-Wiley), who, for a long time, were among the few caretakers of Black art in Rhode Island. The husband-and-wife duo have been nationally recognized artists for more than four decades. They started the theater company in 2000.

The MEO kids started by finding and learning about plants on Narragansett, Pokanoket, Nipmuc, and Wampanoag land, and then used the plants to make dye for costumes. Mixed Magic then taught them about poetry and small performances that they performed to their families at the conclusion of the program two weeks later.

It is unlikely that the collaboration would have happened without the Foundation’s capacity building program. Collaboration, Ayuso believes, makes organizations stronger. It was one of the benefits she pointed out about the program, which is currently in its second (of three) years. Another was how clarifying the strategic communications audit was.

In addition, the unrestricted grant money—each organization receives $30,000 per year for each of the three years—allowed MEO to increase the work hours of operations manager Jordan Schmolka from quarter to half time.

Monteiro used the funds to purchase tablets for their participants’ schooling, which relieves the staff from having to print out 100 textbooks. The money was also used to help with strategic planning for RCP’s board.

Mixed Magic made critical safety changes—such as glass partitions in the musicians’ area to prevent the spread of COVID-19 within the theater as well as allowed the Pitts-Wileys to supplement box office revenue to maintain its Pawtucket space and continue to build more literate and arts-active communities.

“The lack of arts programs in schools is taking a severe toll on us,” Ricardo said while reminiscing about all the talent they used to get from Hope High School and others. “Those kids were our pool and that wasn’t sustained,” added Bernadet.

The program, they collectively said, also gave them the breathing room and opportunity to re-evaluate their operations and incorporate new ways to cater to more generations—such as by having a bigger presence and more marketing on social media to attract younger audiences.

We have to re-invent the living theater experience to be an experience where you have to be there to fully appreciate what we’re doing,” Ricardo said. “Even football—there are people who would rather watch the game on TV than be at the game.”

They don’t have all the answers on how to grow further, but having the other cohort members bounce ideas off certainly helps. Ayuso said years two and three of the program can possibly take a deep dive into one matter each organization is struggling with and help them overcome it.

One thing is certain: this won’t be the last cohort of nonprofits of color that will benefit from this program. All of Rhode Island grows stronger with their longevity.