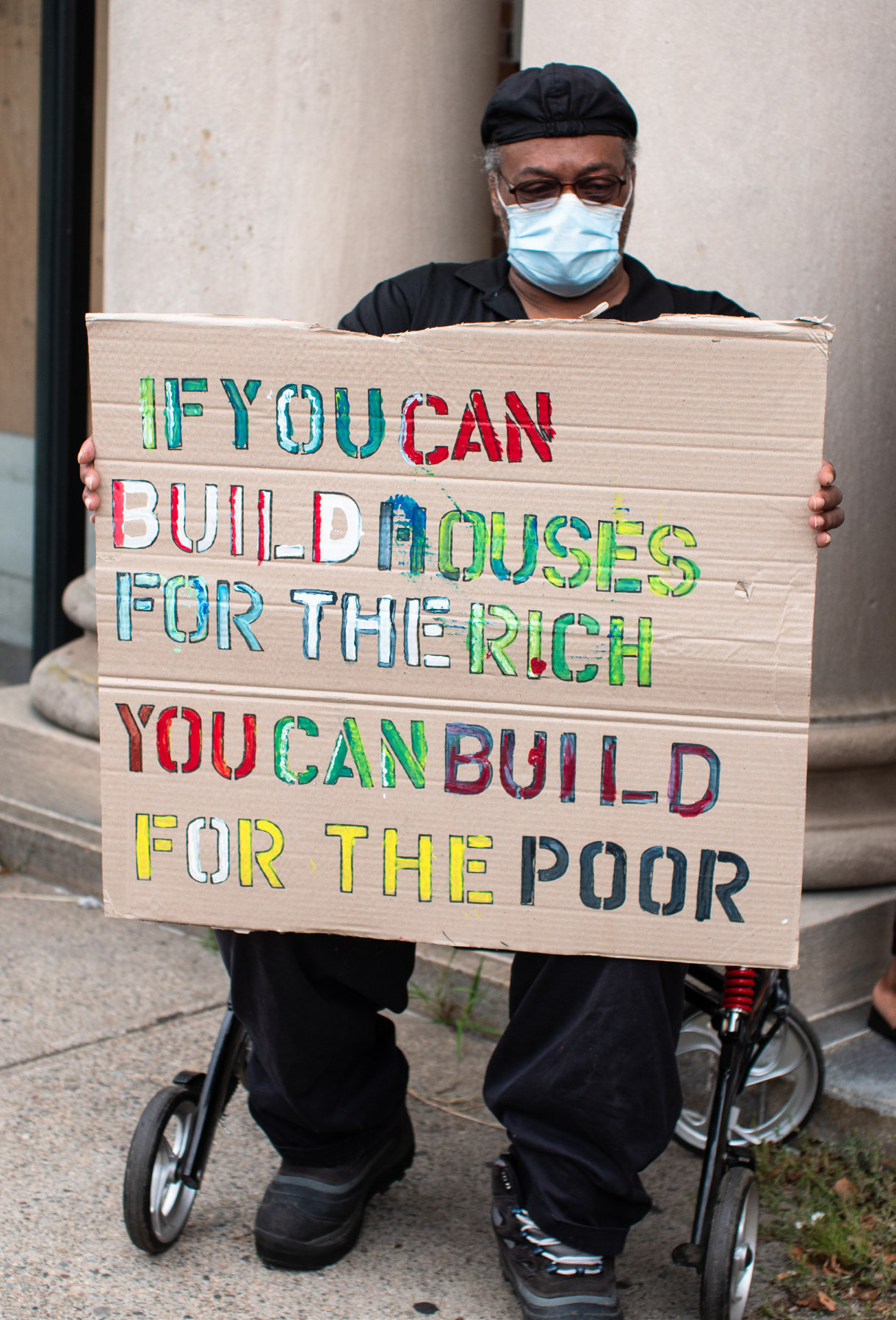

We begin with the challenge that almost everyone of the people we spoke to grappled with: the challenges of housing. In 2022, UCLA’s Williams Institute published a comprehensive report on national housing numbers for LGBTQ+ individuals. They showed increasing housing precarity due to lack of affordability, lower rates of homeownership, and high numbers of homeless LGBTQ+ youth. Continuing discrimination and stigma has made locating housing a community-wide challenge.7 Recent elimination of an exemption that allowed discrimination based on gender identity or expression in owner-occupied buildings is promising, but implementation is a big concern.

In our conversations, participants worried about the lack of affordable housing and how that would shape their prospects in the future. Others had experiences of homelessness and shared the difficulties of finding safe shelters that afforded them a path towards more secure housing. Other respondents shared fears around safe and open end of life options should they need them.

Transgender housing struggles

Data specific to the transgender community reveals that:

32% of respondents experienced some form of housing discrimination including eviction or denial of housing, and 24% had experienced homelessness at one point in their lives—this last number is slightly lower than the national number. National data from the same study notes that only 16% own their own homes, a key marker for stability, while 63% of the general population own homes. Housing is just one part of an individual’s security that also includes economic security, food, and health security. In all, transgender individuals have a more challenging time achieving a basic level of security, even when controlling for age, race, sexual identity, and socioeconomic indicators.9

Across our focus groups, transgender people faced some of the largest hurdles in finding housing. Persistent housing discrimination coupled with work discrimination, left transgender individuals with fewer avenues towards stability.

One transgender person talked about the challenges that awaited them at the large shelter when they needed emergency housing.

“I’ve been in a shelter system… I had to go into an all-male gym. Thank God that…there was an opening and I was able to get out of there within two days, but I had a mat like this [holds up forefinger and thumb to indicate thinness], and I was in a big room. I got into a few fights. I even got a record now because I had to defend myself…It was pretty unsafe at that moment. They did have an LGBT shelter at that time, I was able to thrive from there and now I’m doing much better, but unfortunately, they shut that funding down.”10

Housing concerns connect to all other issues. It was the first concern for most of our respondents. Even if it wasn’t about them specifically, most people understood that security through housing is a fundamental need. In some of the earlier conversations, key leaders in social service organizations pointed out how it is hard for someone to meet their needs without stable housing as a foundation. A direct service provider noted,

“I think it has to start from a housing first model. Because that is one of the fundamental standard determinants of health. And safe and secure housing, and even in Rhode Island, that is still difficult to obtain for trans people, and is especially difficult to obtain for young people.

[We]... need to… talk about gender care, it’s not just about our bodies, or our hormone levels. Gender wellness has to be about the whole scope of our wellness experience. It is influenced by our gender presentation, and how that is broadcast out in society. And so that’s definitely our housing—

when trans people have trouble finding housing because the names on their ID doesn’t match their presentation. Or some people don’t know this, but after you change your name for many years afterwards, your dead name still comes up on your credit score as ‘aka’.”11

Though housing discrimination is outlawed at both the federal and state levels, this does not mean it stops existing. Rhode Island passed anti-discrimination law that included protections for housing (among many other public accommodations ) on the basis of sexual orientation in 1995. Rhode Island updated its anti-discrimination law in 2001 to include gender identity and gender expression, becoming the second state in the US to prohibit discrimination against trans people (it was updated again in 202112).

Many of the organizations that work for the LGBTQ+ community around housing are primarily focused on shelter and other emergency needs, but for the trans community continuing discrimination happens within all forms of housing: shelters, rentals, and ownership. Some felt that an important step would be to have greater advocacy at the state level:

“Here in Rhode Island, we have a problem with affordable housing and…There needs to be a voice in that state house for people like us so that they don’t sweep us under the rug. Same thing with the homeless shelters, there’s no protection for us there. I’ve watched trans people get the crap beat out of them. Do you know what I mean? I’ve seen a lot of stuff. We need more advocates to help us that we’re not thrown under the rug and that’s it.”13

A steady number of local organizations14 offer legal advocacy support for LGBTQ+ populations seeking housing, but access to these services eluded many individuals who were precarious in other social determinants. That is, class15 and racial disparities affect one’s ability to tap into Rhode Island’s existing resources.

Youth housing needs

Housing issues were particularly salient for our younger respondents (and those who work with them). The need for youth shelters are critically lacking for LGBTQ+ youth, who represent a significant percentage of all homeless youth. Just a few organizations (and all located in Providence) provide the bulk of the options in the state. Sojourner House, the first gay and lesbian domestic violence (DV) program, was also the first and only to offer LGBT beds for many years until Haus of Codec recently opened. Youth Pride, Inc (YPI) has a relatively new drop-in/support service and diversion program which indicates how housing is an increased priority for them. And Haus of Codec, which opened up during the pandemic, filled its shelter in a week, and was awarded funding for a second soon afterwards. They announced that they will be opening a new facility with 20 beds in 2023. In 2022 HUD awarded all three of these organizations funding to continue their work on youth housing. Even with these new developments, the need is much greater than what is available. One high school youth expressed the painful housing dilemma for younger people.

“When we talk about housing and funds for housing, we have to remember that whatever effect it’s having on people who are adults…, if you’re 14, and you can’t get a job period, it’s worse. I know people who are stuck in toxic relationships or work for a long time or move from one abusive home to another because they have nowhere else to go, simply because their parents didn’t want them to house because they found that they’re queer.”16

Youth considering or pursuing college and secondary education also spoke about issues they faced in terms of how financial aid might see them. College students who have been disowned by family were often not able to access aid to cover housing if they were still listed as dependents. If they are able to find help for housing in the form of dorms,

“...right before COVID, I was told by my parents that I needed to move out, and quite abruptly…. I feel like, especially as a queer individual, there’s more tension, and more vulnerabilities, and less social support resources because of that marginalized identity. You know, luckily, my parents backed off, but I remember going to RIC and…them offering shelters and then going to the dorms and them saying, yes, you can live here, it’s going to cost this much. It was exorbitantly expensive; I was like there’s no way I can afford this.”17

Another student bemoaned that housing more than their coursework was what stressed them the most, saying:

“As an independent student… I don’t know if I would still be doing school if I didn’t have such a good support system, because, unfortunately...with a couple of relief funds that they have, once you can sign up for them, well, unfortunately, it’s still not enough…I would say it’s the housing bill literally is something that stresses me out way more than the [classes] that I’m taking.”18

In our conversations youth voiced concern over the general cost of housing which left them with few options both before, during, and after college. It made imaging their future a challenge increasingly difficult for this current generation.

Dignity of the life cycle: LGBTQ+ housing for our elders

According to the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), there are over 2.5 million LGBTQ elders living in the U.S. today and it’s estimated that by 2030, 4.7 million will be seeking elderly care and services.19

Our tendency to look at housing as an individual choice means we sometimes fail to appreciate the role that social forces, such as accumulated wealth and discrimination, plays. Obviously, one needs capital to be able to both own and rent.20 Given that wealth is a primary driver of inequality, we need to have better policies that consider long term outcomes for people traditionally left out of the private housing market and we need more imaginative ideas for housing options beyond purchasing. Within the LGBTQ+ people, particularly our older generation, many have been cut off from families as a source of financial support. This in part explains the much lower levels of home ownership in the LGBTQ+ community. The discrimination faced by minoritized and transgender/non-binary individuals combine for even lower rates.

Our families and communities are also an important source of social wealth, in that families serve an important support system as a potential source of both financial wealth and physical/emotional support. For our elders we found this concern to be a dominant one.

“I’m estranged from several of my siblings, and my nieces and nephews. Some of them I don’t even really know very well. So I don’t feel like they’re folks I can necessarily rely on when push comes to shove.”21

Without an extended family, LGBTQ+ people must rely more on the state, organizations set up to assist aging, and chosen kin. For LGBTQ+ people these are often less than ideal, because very few organizations that serve the elderly, particularly in Rhode Island, are prepared to address the needs of the LGBTQ+ community. This has meant that LGBTQ+ people often rely on a more horizontal model of support through chosen families and communities. One older member shares some of the fears of growing older with the state as the only safety net.

“I’m thinking from the perspective of myself as an elder, from an old woman and a lesbian. So, for me housing in this context means, how do I age safely at home? How do I tap into a community? Most of the nursing centers, assisted living facilities, all that kind of stuff are economically out of my reach. …I don’t have kids. So it’s not like that, and I have no blood relatives living anywhere close to me. So it’s me and my wife, and then the community of support I come up with, and that’s scary. ”23

Rhode Island has a number of groups who advocate for our elder LGBTQ+, including Pride in Aging RI (formerly known as SAGE RI) and they have been working across the country to increase housing options for elder LGBTQ+ people. Some people we spoke to feared having to bury their identities should they need to utilize the existing housing options.

“...I mean, aging in housing is so isolating, so depressing, and so lonely. Then when you add in the issues of being LGBTQ+, the fear of having to go back in the closet, in living in communal settings that are not LGBTQ+ friendly, is overwhelming and terrifying.”24

Data from the HRC report on aging shows that 40% of LGBT elders’ social networks have dwindled as they have aged and about 34% of older LGBT people live alone compared to 21% of non-LGBT people.25

The importance of a location where people can age in safety, know that their partners can visit, know that they can be open about who they are is seen as a fundamental issue. Many members of the community have actively worked to build something for aging LGBTQ+ people.

“...I’ve been working for the last 20 years on trying to set up housing for LGBTQ elders. I’ve been working with the same person and have been graced enough to be on a board now of a place called Aldersbridge.”26

In July of 2022, a plan was announced to build affordable, independent living-style housing for LGBTQI+ elders and their allies through a partnership with Aldersbridge Communities, Barbara Sokoloff Associates, and ONE Neighborhood Builders in East Providence. This building will have 39 units available.

For a community that has depended greatly on kinfolk as family, there is a distinctive need for spaces that support the variety of ways that a family can look. How traditional family support systems serve to care for their elders must be reconfigured for the LGBTQ+ community, where the idea of family is often fraught but where chosen families are central to the wellbeing of many.

Footnotes

6. Interview Nov 18, 2021 (13:1; 19)

7. Romero, A.P., Goldberg, S.K., & Vasquez, L.A. (2020). LGBT People and Housing Affordability, Discrimination, and Homelessness. The Williams Institute.

8. These data were the most recent at tiem of research.

9. “Housing and food stress among transgender adults in the United States” by E.R. Henderson, et al., 2019. This study used national BRFSS data.

10. Focus Group July 14, 2021 (18:22; 428 – 432)

11. Interview Nov 10, 2021 (10:12; 77)

12. http://webserver.rilin.state.ri.us/BillText/BillText21/SenateText21/S0563.pdf

13. Focus Group July 14, 2021 (18:12; 283)

14. To name a couple: South Coast Fair Housing and Rhode Island Commission for Human Rights.

15. See recent study by SouthCoast Fair Housing on sources of income discrimination in RI housing: http://southcoastfairhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Its-About-the-Voucher_-Source-of-Income-Discrimination-in-Rhode-Island.pdf

16. Focus Group Nov 22, 2021 (16:8; 100)

17. Focus Group Nov 22, 2021 (16:2; 67)

18. Focus Group Nov 22, 2021 (16:7; 94)

19. Human Rights Campaign. “Long-Term Equality For LGBTQ Elders.” Equality Magazine. 2020. https://issuu.com/humanrightscampaign/docs/equality_winter2020_final/21.

20. More insidiously, housing policies over the past century have allowed certain groups of individuals to purchase and build equity and others to not. This divide has primarily been along racial lines and the effect has been devastating leading to greater inequality and higher levels of segregation across the country. More recently, reports indicate that housing segregation is becoming more fixed along class lines as well.

21. Focus Group July 29, 2021 (15:12; 189)

22. Singleton, M. C., & Enguidanos, S. M. (2022). Exploration of Demographic Differences in Past and Anticipated Future Care Experiences of Older Sexual Minority Adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(9), 70–87. This article details the different needs within the aging LGBTQ+ community. See a recent article on the ways in which “chosen family” represents the main support network for LGBTQ+ elders. KNAUER, N. J. (2016). LGBT OLDER ADULTS, CHOSEN FAMILY, AND CAREGIVING. Journal of Law and Religion, 31(2), 150–168. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26336669. Another recent study looked at the social strength that already exists in the older LGBTQ+ community (Wardecker BM, Matsick JL. Families of Choice and Community Connectedness: A Brief Guide to the Social Strengths of LGBTQ Older Adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2020 Feb 1;46(2):5-8.)

23. Focus Group July 29, 2021 (15:3; 89)

24. Focus Group Nov 14, 2021 (5:4; 43) in FG_ LGBTQ+ Action RI

25. Human Rights Campaign. “Long-Term Equality For LGBTQ Elders.” Equality Magazine. 2020. https://issuu.com/humanrightscampaign/docs/equality_winter2020_final/21. ;

26. As of summer of 2022 Alderbridge Communities will soon offer an affordable apartment community for LGBTQ+ elders (https://www.aldersbridge.org/aldersbridge-communities-to-bring-affordable-housing-to-lgbtq-elder-population/) ; Focus Group Nov 14, 2021 (5:3; 37). The Rhode Island Foundation provided a $25k grant to Aldersbridge Communities for the LGBTQ+ Affordable Housing project. The grant supported a feasibility study for the development of 50 units of affordable housing.

Health & wellness

When we consider health and wellness there are three broad categories we need to address: first is the question of: access/competency, support, and lastly are particular health needs and outcomes for and within the LGBTQ+ community.